Past nuclear dismantlement efforts – from Libya to the Soviet Union – offer clues about what Iran might do next.

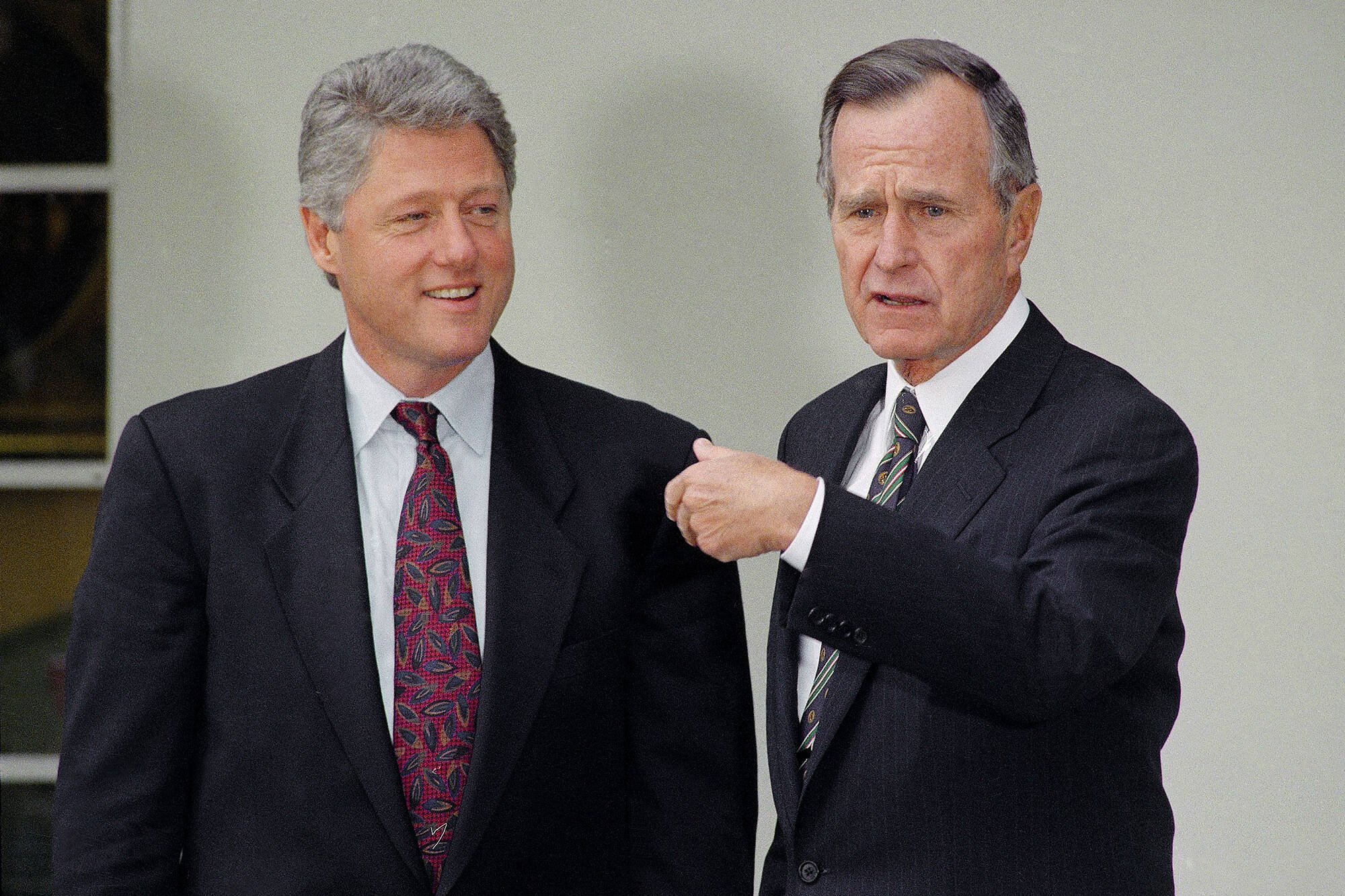

The U.S. and Iran have once again opened talks on Iran’s nuclear program, with President Trump intent on preventing Tehran from getting a nuclear weapon.

Negotiators are still in the earliest stages of talks, so there’s no way to know whether a deal will come about or what it would look like.

RELATED: Iran Nuclear Talks: Where Do the American People Stand?

But this is not the first time America has engaged in nuclear dismantlement discussions with another country. Here are four previous cases – with varying degrees of success – that could paint a picture of how dismantlement will go for Iran.

Libya

By 2003, intelligence analysts believed Libya was only five years away from building its first nuclear weapon. The country had long been sanctioned by the west for its support of terrorism, and its dictator – Muammar Gaddafi – was reportedly racing to complete nuclear and chemical weapons of mass destruction to cement his power.

Libya secretly negotiated a deal with the U.S. and the U.K., agreeing to dismantle their weapons programs in exchange for the west lifting sanctions. Gaddafi announced the agreement in December 2003 and began allowing international agencies in to monitor the dismantling. By April 2004, the U.S. lifted its sanctions against Libya.

Gaddafi mostly complied with the dismantling agreements over the next few years. But in 2011, a civil war erupted, and NATO – led by the U.S. – intervened to protect civilians from violence by the Gaddafi regime. Libyan rebels ended up toppling the regime and executing Gaddafi, a fact that North Korea cited as a reason to resist nuclear dismantlement.

The Soviet Union

By the time the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, it had 35,000 nuclear weapons stockpiled all across Eurasia. When the dust settled and the borders were redrawn, four countries – Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus – possessed Soviet nukes.

Belarus had around 500 nuclear weapons left over. As a close ally of Moscow, Belarus willingly complied with Russia’s request to recoup the weapons.

Kazakhstan inherited 1,400 nuclear warheads, but Kazakh leaders wanted to maintain good relationships with the U.S. and Europe, so they agreed to ship all of their weapons to Russia for dismantlement.

Ukraine was the most sensitive case.

Having a fraught history with Russia, Ukraine was reluctant to give up their roughly 2,000 nuclear warheads, wanting them instead as a deterrent against Moscow. With the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, Ukraine reluctantly gave up its arsenal in exchange for security assurances from Russia, the U.S., and the U.K.

Ultimately, Russia violated the agreement in 2014 when it annexed Crimea, and again in 2022 when it launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Iraq

In the late 1970s, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein began pursuing nuclear weapons that military analysts believed would have been ready by the mid-1990s. Hussein may have used the weapons to threaten Iran or America’s allies in Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Iraq never got to develop nuclear weapons. In 1981, Israel bombed Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor, which Israelis officials claimed set back Iraq’s nuclear weapons capabilities.

A few years later in 1990, with the country’s economy struggling, Hussein invaded and annexed Iraq’s small-but-wealthy neighbor Kuwait. A coalition of 42 countries, led by the U.S., intervened in what became known as the Gulf War and liberated Kuwait in just over a month. As part of the ceasefire, Iraq’s nuclear weapons program was destroyed, never to be resurrected.

South Africa

South Africa remains the only country to ever build and then voluntarily dismantle its own nuclear weapons.

In the 1980s, South Africa’s apartheid government secretly built six nuclear weapons, convinced it needed a deterrent against what it called a “Total Onslaught” from Soviet-backed forces in the region. By 1989, it became clear that the apartheid regime could not stay in power much longer, and President F. W. de Klerk decided the nukes were more of a liability than an asset. All six bombs were dismantled in 1990.

Related

Peyton Lofton

Peyton Lofton is Senior Policy Analyst at No Labels and has spent his career writing for the common sense majority. His work has appeared in the Washington Examiner, RealClearPolicy, and the South Florida Sun Sentinel. Peyton holds a degree in political science from Tulane University.