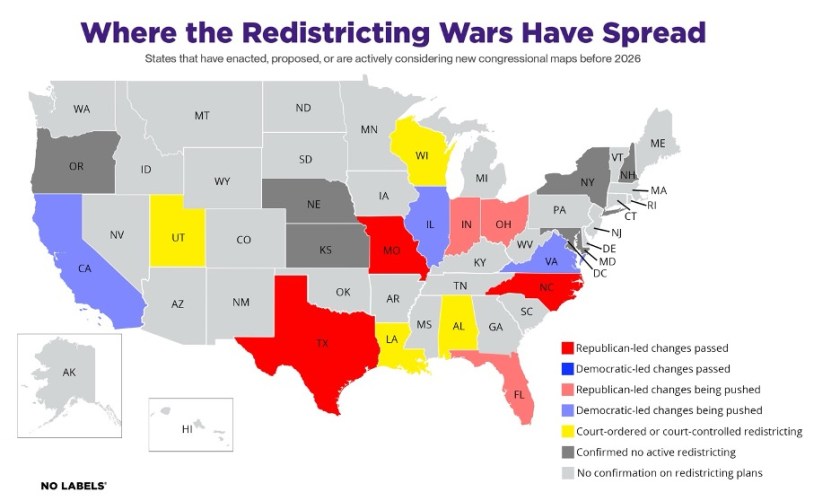

An effort to redraw congressional districts in Texas has now spread to states across the country. Here is where things stand.

Redrawing congressional maps has traditionally happened once a decade, right after the Census. That norm is breaking. In 2025, both parties are pushing to redraw House districts mid-decade, not because the law requires it, but because the balance of power in Congress is so close that even a few newly drawn seats could decide who controls the chamber.

This effort arguably began in Austin, Texas. After Donald Trump called on Republican-led states to shore up GOP majorities ahead of the 2026 midterms, Texas state lawmakers approved a new congressional map. The plan was signed into law by Governor Greg Abbot on August 29 and is projected to make it easier for Republicans to win as many as five Democratic-held seats in the 2026 midterms. That same week, Democrats in California introduced their own new map, designed to target five Republican-held seats. Because California normally relies on an independent commission to draw its districts, that plan will only take effect if voters approve it through a ballot measure, Proposition 50, on November 4.

Since those two moves, other states have followed. North Carolina passed a new map in late October that favors Republicans and weakens the state’s remaining Democratic swing district. In Missouri, Republicans approved a new map that would likely shift the balance from six-to-two Republican to seven-to-one, though that map is now facing a referendum challenge.

Elsewhere, redistricting efforts are underway or being debated. In Indiana, lawmakers have scheduled a special session to consider a new map. In Illinois, Democrats are weighing changes that would eliminate one of the state’s three Republican seats. Florida, Kansas, and Virginia are also considering changes, while Ohio is required to pass a new map this year under a voter-approved constitutional amendment. Each of these efforts is rooted in a common calculation: if the map can be redrawn now, there may be fewer competitive seats to worry about later.

This kind of mid-decade redistricting used to be rare. Between 1970 and 2020, only two states, Texas in 2003 and Georgia in 2005, voluntarily redrew their congressional maps in the middle of a decade for partisan reasons. Today, more than a dozen states are considering or implementing changes well ahead of the next census. Some are acting through the courts, others through ballot initiatives, and many through state legislatures.

The implications are significant. If the most aggressive Republican maps take effect, they could net the GOP as many as nine new seats. On the Democratic side, maps in California, Illinois, and Maryland could add several back, but the net result would likely benefit Republican control of Congress. That range of possible outcomes, roughly ten seats, matches the current margin of control in the U.S. House.

Litigation is already underway in several states, including Texas, Missouri, and North Carolina, and more is expected. In some cases, courts may allow the new maps to stand. In others, they may reject them for violating state laws or constitutional protections. And in California, voters will decide the outcome directly when they vote on Proposition 50.

This is not a once-a-decade process anymore, but an active political battle playing out state by state, with both parties participating and the stakes tied directly to the makeup of the next Congress. Congressional districts that were drawn just a few years ago are being redrawn again. In some places, the lines used in 2026 may be different from those used in 2024.

One state that is running counter to this trend is Utah, where a court ruled that the Legislature’s 2021 map violated the state’s anti-gerrymandering rules and ordered new, fairer lines drawn for 2026. Not every state legislature is on board. Despite sustained pressure from the White House, a number of GOP state leaders have resisted mid-decade redistricting, which shows the practical limits of national pressure on veteran legislators in safe seats.

To help make sense of it, we have created a map showing where new congressional maps have already been passed, where states are actively considering changes, and which party is leading the effort in each case. The landscape is still shifting, and some of these efforts may not succeed. But taken together, they represent the largest wave of mid-decade redistricting in modern American history.

Related

Sam Zickar

Sam Zickar is Senior Writer at No Labels. He earned a degree in Modern History and International Relations from the University of St Andrews and previously worked in various writing and communications roles in Congress. He lives in the Washington, D.C. area and enjoys exercise and spending time in nature.

You must be logged in to post a comment.